Thomas Carothers, a leading authority on international support for democracy, human rights, governance, the rule of law, and civil society, directs the Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Programme of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What would be your assessment of the state of liberal democracy 30 years after the fall of the Iron Courtain in the CEE space?

Thomas Carothers: The state of liberal democracy in CEE is probably worse than we hoped but better than we feared. It is in an intermediate state in quite a few countries and, viewed through a broad historical lens, this is probably similar in some way to the democracy progress that Western Europe saw in the late nineteenth century and in the first half of the twentieth century. But because the expectations were so high, and because communications today are much more advanced, that feels slow and frustrating.

There is no underlying democratic destiny that is assured. It was also not assured in Western Europe, but historical forces managed to align so it worked out. So it is not that Central and Eastern Europe is on a Western European path. It is on its own path, which may have its own outcomes.

Could we point to some of the lessons learnt during this democratising journey that show what the West should have taken into consideration?

TC: I guess in terms of the things that we didn’t understand in 1989, a central lesson is the relationship between achieving political pluralism and achieving an effective state and rule of law. These are two different things. We had a rush of pluralism into the region – multiparty elections and freedom – but we had very corrupt states, the transformation of which has been very problematic, particularly the rule of law.

The socialist system of the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s had a certain amount of administrative regularity and bureaucratic structures, but they were not very lawful states in a deeper sense. On one hand, the socialist systems were not very good at constraining power holders through law. The power holders saw themselves as making the law rather than being subject to the law. On the other side, ordinary citizens often experienced socialism as involving a lot of illegality and unfairness regarding who got certain resources or who got access to certain information. Both of those legacies transferred into the post-communist era in a powerful way.

Thomas Carothers. Photo: Courtesy of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Achieving constraint on power holders by law and the experience of lawfulness for citizens, as really regulating both their interactions with the state and their perceptions of the state, has really been difficult. So we have high pluralism and problematic law. This is essentially a condition more characteristic of certain parts of the developing world than of Western Europe.

Latin America has had this for a long time – an area with a high degree of freedom but poorly functioning states. I am not equating the states in CEE with the states in Latin America, but the condition of the relatively poor rule of law with high pluralism has been characteristic of other places that have seen fluctuations in democracy as a result, as well as some of the trends towards the illiberal populism that we see in Central Europe.

Is this democratic retreat an expectable disease of a still young democracy? In other words, is this as good as it gets, with the downsides manageable?

TC: There is still the possibility of better things being achieved. This unpleasant halfway state that most of the countries in the region feel doesn’t have to be a permanent destiny. Things could get better because citizens can over time constrain power holders with law and illiberal forces that want to capture systems, particularly in reaction to socio-cultural change, could fade away. It is an ongoing struggle.

The 1990s were heralded as the age of the end of history, the age of liberal democracy. 30 years later its legacy is contested, we are talking increasingly of an age of illiberalism. What were the domestic conditions and factors that made the illiberal turn possible within the CEE countries?

TC: There are a few particularities in the case of Hungary. Unlike Poland, Hungary was very badly hit by the financial crisis in 2008, which devastated the socialists and left the political field open, in the sense that there was only one alternative.

Secondly, Hungary had some structural features of a political system that allowed a leader who got 50-51% of the vote to get a super-majority in the parliament. Once you have a super-majority in the parliament you can reshape the political regime – modify the Constitution, the fundamental electoral and media laws. The Hungarian system played a certain role that has not occurred elsewhere in the region.

Lastly, Hungary does have this lingering territorial sense of failure from the first half of the twentieth century, that allows a kind of a nationalist narrative where the Treaty of Trianon remains a terrible experience. Compared with any other CEE countries, Hungary is able to project a powerful national narrative of redemption and humiliation in the twentieth century – the loss of territory and citizens.

One powerful commonality is the failure of the centre-left in both Poland and Hungary to really achieve the promise of the 1990s. During those times many Central Europeans embraced the centre-left because they wanted social protection with some market capitalism that would provide growth.

They wanted the best of both worlds: capitalist economies that would catch up with Western Europe, but also German-style social protection. That was not really possible. It was a nice idea but very difficult to achieve, because what happened was that Central Europe moved quickly on the social protection front, and people began expecting a level of social benefits that the countries couldn’t really afford.

The kind of quick political similarities between Central Europe and Western Europe made people think they should also get a quick catch-up economically. If we look at other countries’ relatively rapid catchingup to Western European levels, like South Korea, Taiwan or Chile, they went through a long sustained period of tough neoliberalism so that the citizens had to experience fairly hard working conditions for a long time before they got to social protection. So the failure of the centre-left helped a lot.

A second commonality is the citizens’ experience of power and law. I was really struck in the early 1990s in Central Europe how people came out of the experience of socialism with a contradictory psychological state – a tremendous suspicion of power, but at the same time a tremendous desire for security and to be taken care of. What happened was that the experience of capitalism, transferred from the experience of socialism, was so much dirtier than people expected or hoped. This whole perception of dirty deals, crony capitalism, very opaque power, was very disillusioning.

This continued experience of dirty and opaque power prepared the ground for an illiberal nationalist demagogue who says that we need to take over the system and really make it work for the people. The reference to the people and the power of that idea comes from the experience of the people being frustrated with what they got and from a sense of betrayal.

A third commonality is social change. Central Europe coming out of the 1980s was in a very different socio-cultural state than the Netherlands, Belgium, France or Germany in terms of the liberalism of society, attitudes towards the role of women, LGBT issues or religion.

Some parts of society caught up very quickly, whereas other parts, preponderant in more rural areas, were rejecting it. The socialist systems were very puritan and conservative in that regard, and did not prepare the people for such a transformation. So you had this rapid socio-cultural change that led to a vulnerability of society to a counter-reaction in which politicians could come to certain voters to say “too much, too fast”.

How should illiberalism be understood in practice? What are the illiberals rejecting first and foremost in a liberal democracy?

TC: A certain combination of things seems to occur. The first is either a strong political leader or a strong political party has a powerful narrative, which tends to be a nationalist one (strengthening the country’s resistance to attacks from abroad so it emphasises national strength, national unity and resistance to foreigners).

These messages are the seeds of illiberalism, because the national unity implies that opposition is disloyal, that this is the true national project, so if you are not with this project you are actually against the nation. So the first trait is to de-legitimate the political opposition through such a narrative. The second trait is to de-legitimate international pressure on values, principles and norms. If the EU does something against us, that is because they don’t support our nation.

In CEE we have high pluralism and problematic rule of law. This is a condition more characteristic of certain parts of the developing world, that have seen fluctuations in democracy and trends towards illiberal populism.

To sum up, there is a narrative that is strong, widely appealing, designed to resist opposition and international pressure. It is usually a political narrative rooted both in socio-cultural as well as sociopolitical values. They are speaking about the nation as a cultural entity which is higher than any political system and principles.

They are putting the nation as a cultural idea, an entity above political principles, and that allows them to subvert political institutions for the sake of the national project. Therefore if the judiciary has not been true to the national project, then that is a disloyal judiciary.

One of the things illiberalism has to do is to horizontally subvert all checks and balances on the system, and it needs a justification for doing that. Usually the judiciary is the biggest threat because it exerts the biggest constraint on power; and then the opposition parties that you try to discredit; and then the media.

A crucial part of the illiberal project is what we would call crony capitalism, the co-opting of the business sector, and weakening any independence of the business sector by bringing them in and insisting on a kind of relationship of control. They put them in positions of directors of banks or presidents of companies who are loyal to the party, so you are weakening the independence of the business sector.

Sometimes it seems we are forgetting basic notions. Democracy in its modern sense is liberal democracy. But today the notion of “liberal” has become highly politicised, it has a very ideological connotation. So what is the classical meaning of liberal democracy?

TC: Liberal democracy is a democracy that combines the voice of the people with constraints on government power, in terms of respect for political and civil rights which allow people the protection of the rights of minorities and constraints on power through law. A democracy without liberalism is an unconstrained democracy, that becomes a reckless democracy which takes over the institutions and becomes unconstrained power. Liberal democracy is a democracy that is constrained and regulated in positive ways.

To what extent were the economic and migration crises enablers of the illiberal moment?

TC: I think that is a good way to look at it. You had vulnerabilities which were triggered by events. If you were already unhappy with the capitalist system, the financial crisis convinced you that it was a rotten system. And the migrant crisis highlighted the socio-cultural fears and made you feel that we’ve gone too far; this was the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

That’s why it is important to see what is happening as largely a reactive trend, which could dissipate if the structural events don’t repeat themselves and gradually fade away. There have been years of slow growth, the migrant crisis has died down, but now the illiberals are trying to take credit for the growth that has occurred, and are trying to continue to stir up social crises. We are still in the midst of these battles, but they don’t have any new tools.

In their forthcoming book, Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes point out that the surge of ethno-politics in Central and Eastern Europe “has its origins in political psychology, not political theory.” So should we see the roots of this illiberal pivot in the realm of psychology?

TC: Politics is always psychological. Hitler’s rise in the 1930s is also about the psychology of grievances in Weimar Germany and the sense of frustration internalised at that time. Powerful political movements are always psychological movements because the leaders are telling a story or a narrative that stirs people.

I think what Ivan and Stephen are reacting to is a sort of explanation that would say that a certain level of GDP growth will ensure a certain result or a certain level of political freedom, and saying that underneath are always deep psychological waters and vulnerabilities. The problem of the West is that the mainstream view of progress and the liberal destiny of the West is not as pointed as the alternative narrative of anger and nationalism.

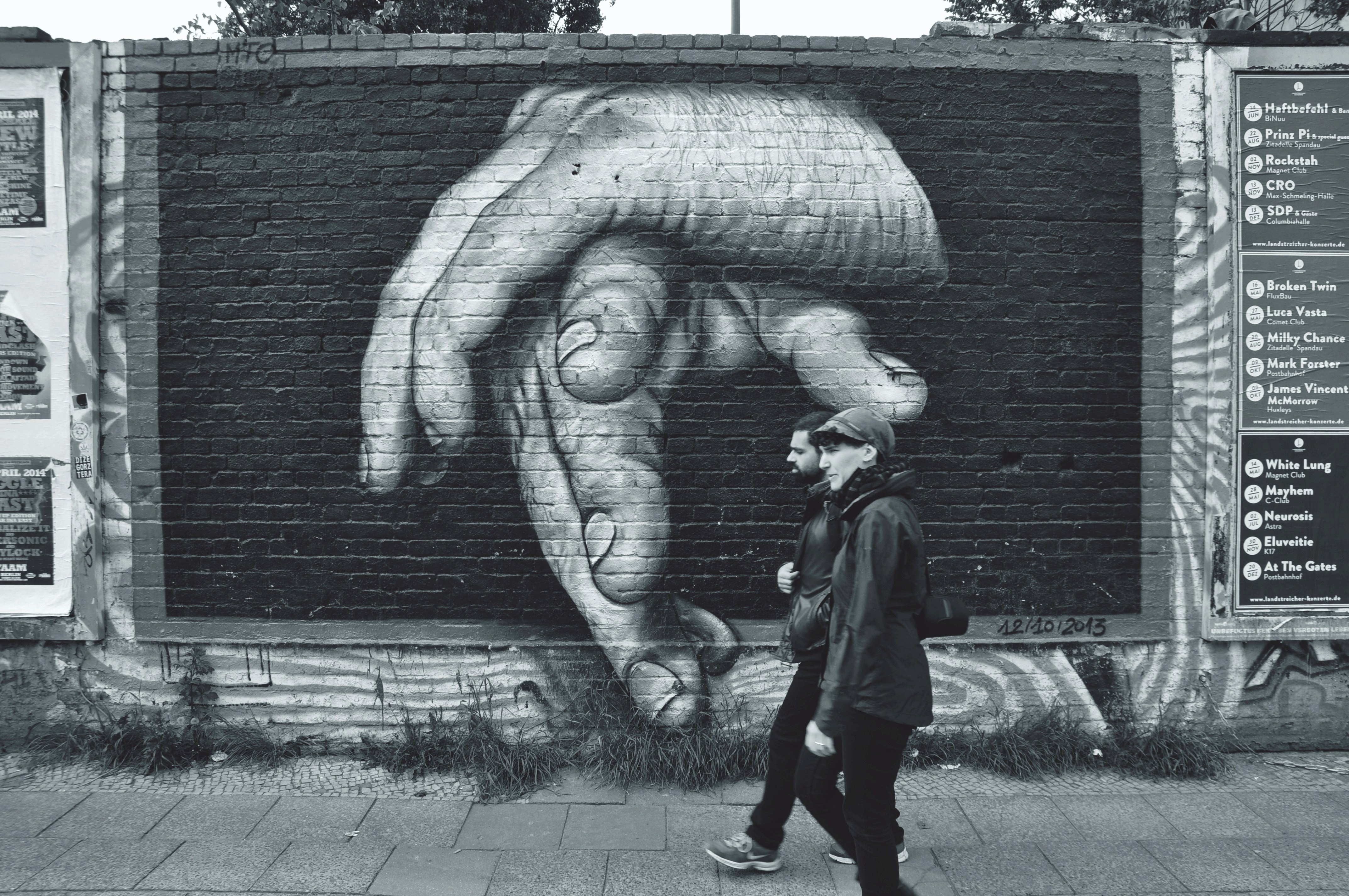

© Photo by Casimiro PT on Shutterstock

The current resurgence of nationalism is both a domestic and an international phenomenon. It is domestic in the sense that in many countries nationalism is part of a socio-cultural agenda that is very conservative, that says we want to go back on changes that came from outside (either in the form of people or in the form of ideas), and nationalism is a platform to resist that transnational influence.

The civic nationalism isn’t under threat only in the illiberal parts of CEE, but also in the heart of the civic nationalism, in UK, Italy or France. This isn’t an East-West issue anymore but within democracies. Nationalism is kind of the flavour of the moment because it catches all these different trends – the socio-cultural changes and the economic changes.

Liberal forces need to regroup and re-energise themselves and think about what we are not offering to people that we offered before; we need to bridge these divides within society, we need to hear people’s concerns about social change, we need to understand the need for more inclusive economies.

Liberal democracy won’t win just by saying we are waiting for you to fail with your illiberal project and then we will be back. Everywhere liberals have to prove to sceptical publics that they can deliver the things that they delivered before.