Q: Traditionally, Germany has projected a sense of reluctance to the exercise of power – the image of the ‘unready hegemon’. By leading and shaping the future Commission, has Germany become ready to lead? Is this a change of historical paradigm? You were one of the voices that, in 2011, said “I fear Germany’s power less than her inactivity”.

A: The view that Germany has been reluctant to use its power is controversial. For example, some of our Polish nationalists refer to the European Union as the German Reich. Even government officials talk about Germany’s over-using its size in the European Union. My own take is that Germany is, of course, the largest shareholder in this business, but it doesn’t have a controlling stake. Germany has about 20%, and after the UK’s departure, Germany will have 25%, to France’s 16% and Poland’s 7%.

It is much easier for Germany to put together a blocking coalition or a positive coalition, but it does not have an automatic right of veto. Germany does need others. I wish Poland was in that group representing our region. The alternative, which our current government doesn’t seem to realise, is that Germany might act as the centre of the wheel, with spokes projecting out from Berlin, which is a worse position for smaller countries such as ours. Those are some of the choices that governments make in their national strategies. Now that for the first time in history Germany has received the post of the President of the European Council, I agree with you that it should be extra-sensitive and lean backwards.

Q: There is this perception that the CEE countries were completely bypassed in the most influential jobs – the leadership of the Commission, the European Central Bank, the European Council, or High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The political & geographical symbolism cannot be avoided. Is the balance of power/influence shifting towards Old Europe/the eurozone core?

A: It is not a perception, it is a reality. But the cause of this is the extraordinarily inept way in which some governments negotiated the personnel decisions. The Polish government achieved its aim of blocking Frans Timmermans. Well, if you set yourself this objective, then of course it is a success. But the price of such a success is that you get nothing in return.

Will this emerging reality alienate and create frictions with New Europe? Will the gap and resentment between Old and New Europe increase? How can this gap be closed? It is like institutionalising a multi-speed Europe by default.

Firstly let’s remember what happened and why. Secondly, I hope the lesson is learned. If you are motivated by purely negative motives, you get a negative outcome. And if you set yourself unrealistic goals, you often fail.

In the Council, the current Polish government set itself two goals: a) not giving Tusk a second term and b) replacing Tusk with another Pole. Of course, those two objectives taken together were impossible to fulfil. We are in the end a club of democracies where some things are decided super-democratically by consensus and unanimity, others very democratically by super-majority, and yet others by a straight majority. You have to navigate within these rules, and for every decision you have to rally around either a blocking or a positive coalition advise the new man, I would say, ‘pick a couple of issues – one in each neighbourhood – and focus like a laser beam on their implementation’. We need to establish the credibility of the office. Nothing succeeds like success.

Q: In a time when there is no common understanding on what strategic autonomy should be, is Europe ready to embrace the reality of the return of great-power competition? Should it embrace it?

A: It is necessary, but that doesn’t mean we will stand up to the challenge. The stakes are – in the military sphere, the cyber-sphere, the trade sphere – whether we will live by rules that we negotiate with other great power centres, or by rules that others impose on us. If we have enough foresight and enough cohesion, in due course we will reap the benefits of being one of the three big powers in the world. If we don’t, if we allow ourselves to be fragmented, then we will be subcontractors for others in every sense of the word. And subcontractors don’t get the big profits.

Q: Initially it was speculated that the choice of von der Leyen as opposed to Timmermans could be a compromise on the rule of law principle and an appeasement to V4 to avoid dealing with their obstructionist behaviour. Should we expect the same pressure on the rule of law issues as in the past?

A: First of all we should not accept the nationalist authoritarian narrative that expecting the observance of treaties and the rule of law is some kind of sanction or repression towards any member state. Timmermans was not attacking Poland, but helping to defend Poland’s constitution. It is in the interest of the people of Poland and Hungary to be ruled democratically, according to their own constitution, in accordance with the ratified treaties and with the European ways of doing things, including the Copenhagen criteria (which we had to fulfil before joining the EU) of having a competitive democratic system. In her speech, which I witnessed in Strasbourg, Ms von der Leyen said that there would be ‘zero tolerance’ on rule of law issues. It is a commitment made because of reasons of principle and also for reasons of politics. In the end the pro-European parties (socialists, greens, EPP) have more votes than the nationalists and I don’t think it would be wise for her to lose their support and therefore that of the majority.

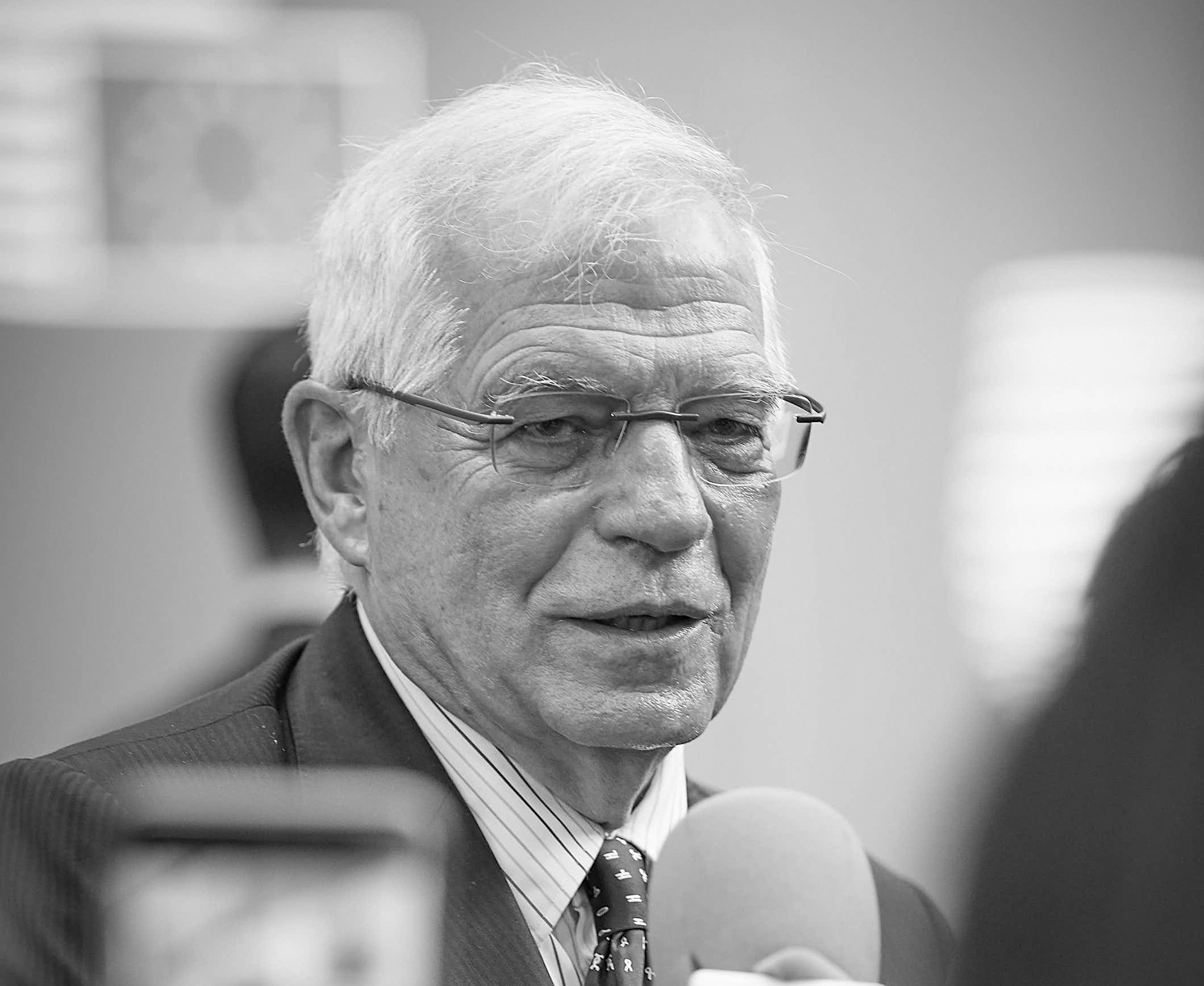

Q:It is interesting to observe, as Carl Bildt has pointed out, that “of the four High Representatives of the EU since the position was created, half will have been from (the Socialist party of) Spain.” Does this tell us anything about the direction of the EU’s Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and its forthcoming (geographical) priorities? What would be reassuring for the CEE members?

A: I don’t really know enough about Mr. Borrell, but I hope he doesn’t make the mistake of Federica Mogherini, who visited Cuba twice as often as Ukraine. I hope he shows the eastern flank that he cares equally for our southern and eastern neighbourhoods. If I were to advise the new man, I would say, ‘pick a couple of issues – one in each neighbourhood – and focus like a laser beam on their implementation’. We need to establish the credibility of the office. Nothing succeeds like success.

Q: In a time when there is no common understanding on what strategic autonomy should be, is Europe ready to embrace the reality of the return of great-power competition? Should it embrace it?

A:It is necessary, but that doesn’t mean we will stand up to the challenge. The stakes are – in the military sphere, the cyber-sphere, the trade sphere – whether we will live by rules that we negotiate with other great power centres, or by rules that others impose on us. If we have enough foresight and enough cohesion, in due course we will reap the benefits of being one of the three big powers in the world. If we don’t, if we allow ourselves to be fragmented, then we will be subcontractors for others in every sense of the word. And subcontractors don’t get the big profits.

Q: Where do you think that the trans-Atlantic relationship is going, especially if we look at the current disagreements related to Iran, to maintaining the JCPOA, and the other profound frictions?

A: On Iran it is relatively easy. If Europe has to choose between Iran and the United States, we know how we will choose. It will be much harder on China, because China is so important to our economy, to our export industries. I would caution our American friends that just because you have managed to bring the European companies that were trading with Iran to heel, that doesn’t mean that the trick will work the same way in their confrontation with China. This needs a pan-Western solution, which is why I’ve been advocating the rebirth of COCOM– the

Coordinating Committee for the transfer of technologies, investments and trade. If the rivalry between the United States and China is the organising principle of this century, then the US needs us as an ally – but we are too important to be just told what to do. There has to be a negotiation of how we go about it.