March 2023

Some of the most important politicians and parties in Romania have long been flirting with nationalist, ultraconservative and anti-Western discourse. Traditionally, mainstream parties recruited politicians (like radical nationalists Adrian Păunescu[1] or Codrin Ștefănescu[2] and ultraconservative[3] Leon Dănăilă[4]) as a way to attract radical votes but gave them little or no political power.

Later, new generations of radical and far right politicians started to gain actual power in the two major parties. For a while the Liberals put forth Marian Munteanu, accused of fascism and antisemitism, as a candidate for Mayor of Bucharest; they also recruited nationalist media personality Rareș Bogdan as the first name on the candidate list in the 2019 European elections. Under the leadership of Victor Ponta, the Social Democrats took a nationalist turn since the 2020 presidential elections, under the slogan “Proud to be Romanian”[5]. Mr Ponta’s successor, Liviu Dragnea, took an even more nationalistic and explicitly anti-Western turn, in part to deal with the backlash from his corrupt dealings and efforts to change the Penal Code to suit his interests[6],, which were condemned by Brussels and Washington, as well as by domestic reformist and democratic forces.

For a while, things seemed to improve, Ponta and Dragnea lost elections and power in the Social Democrat Party and moved on to form small, borderline irrelevant, nationalistic parties. Liberal Klaus Iohannis, an ethnic German, won comfortably two consecutive presidential mandates. Also, the current governmental grand coalition between the Liberals and the Social Democrats discouraged both parties from radical adventures.

This period of relative moderation seems to be ending abruptly. Since December 2022, mainstream politicians have been taking over narratives and messages from far-right and anti-Ukraine forces on at least three major occasions. These include the debate about Romania’s denied entry to the Schengen space[7], the debate about Ukraine’s new law regarding minorities[8] and the ongoing discussions about alleged Ukrainian actions of deepening the Bystroye Canal[9]. The Social Democrats have been most active in this respect but the Liberals also played a role through the imprudent positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs[10] and through radical politicians like Rareș Bogdan.

In all three circumstances Romania had a legitimate grievance. The country meets the Schengen criteria and has been denied entry on political reasons; the Ukraine minorities law does not, arguably, meet European criteria; finally, the Bystroye canal is part of a longstanding dispute with Ukraine where Romania has repeatedly been able to use international law to block Ukraine’s ambitions.

Thus, a response from the authorities and political parties was necessary to prevent radical forces – like the far-right anti-Ukraine party AUR and its leader George Simion – from taking over the subject. But such a response should have been proportional, prudent (given the ongoing war) and, more importantly, rooted in values like liberal-democracy and respect for international law. The discourse of the major political figures included such moderate messages but combined them with messages that were partially or entirely aligned with the discourse of the far-right, anti-Ukraine forces, as we will see in this report. This was a mistake.

If mainstream politicians hoped to outmanoeuvre AUR and its president George Simion, they were extremely wrong. Simion got exposure using the scandals; his messages were implicitly legitimised as a more colourful version of what most politicians and the MFA were saying. On social media, the marginalisation of mainstream politicians was even stronger: channels from the ecosystem of AUR dominated the debate, drawing more engagement[11] than all other parties combined, while moderate voices like president Iohannis and Liberal PM Ciucă drew very little engagement.

Thus, mainstream politicians have strengthened the far-right anti-Ukraine discourse; in the 2024 elections this may come to haunt them. Once parts of the electorate get to radicalise, they may well choose the original (AUR) rather than the copycats (Social-Democrats, Liberals).

What is next? Of the three events we discussed, the minority laws seem to have had limited impact of any kind, while the Schengen and the Bystroye scandals have clearly benefited AUR and the far-right, pro-Kremlin ecosystem. Also, polls show broad, albeit slowly diminishing support for the cause of Ukraine and the refugees. Under these circumstances a rational political operative would reverse course. However, Romanian politicians have showed an inclination towards the ignorance of reality and pandering to nationalists and ultraconservatives; this has led to past fiascos like the aforementioned episode involving Marian Munteanu[12] in 2016 or support for a referendum in 2018 to enshrine „traditional” heterosexual marriage in the constitution[13] that failed despite support from both Liberals and Social-Democrats. As such, there is a strong possibility that mainstream politicians will double down their efforts in the hope that they may eventually have an impact. Such a strategy will not mean that Romania will curtail its support for Ukraine, but rather that major politicians will continue to signal their displeasure in providing such support[14].

This would only add fuel to the far-right and Kremlin-aligned forces. Throughout 2022, AUR and the Kremlin-aligned conservative actors were having a hard time trying to support the Kremlin while at the same time not incurring criticism from a public that is fundamentally hostile to Russian imperial ambitions. A more hostile position towards Ukraine from large parts of the political establishment would be the perfect way out this dilemma. The far-right would suddenly be able to criticise Ukraine without appearing pro-Kremlin.

Even if

mainstream politicians were to eventually give up this strategy, under pressure

from the President or from foreign partners, the harm would already be done.

Their re-conversion to moderation would appear insincere, strengthening the

far-right, Kremlin aligned actors, undermining Romania’s pro-Western

orientation and its commitment to liberal, European values and creating a more

fragile strategic alignment (since foreign policy and security decision-making

would potentially not rely anymore on wide support from either the political

class or society at large), at a time when Russia is likely to step up its

political warfare and manipulation aimed at widening divisions among

Euro-Atlantic allies and within individual countries. This is a trend that is

only picking up these days as we head into the pre-electoral season leading up

to 2024 as an election year across Europe.

Case Study 1: Mainstream reactions to the Schengen debate

In a previous report, we have discussed how during the Schengen debates[15] radical politicians were widely present in the public debate and authoritatively dominated the debate in social media[16]. We argued, without entering into detail, that a significant cause for this was the failure of the mainstream politicians to provide a form of criticism towards Austria that would be assertive, yet still fully anchored in Euro-Atlantic values. In this report we show how major mainstream politicians actually promoted a discourse that was on occasion very similar to nationalist and anti-Western discourse.

The president and the prime minister who coordinate and, respectively, implement Romania’s foreign policy were generally prudent in their declarations, focusing more on avoiding blame on themselves[17] than finding culprits. Still, neither of them directly censored ministers or ‘liberal’ politicians taking radical stances.

Klaus Iohannis, a Romania-born German ethnic, is second term president of Romania and former leader of the Liberals (EPP). He has historically been seen as a voice of moderation and, in this crisis, he generally avoided nationalist overtones. Nicolae Ciucă , a retired general, is the current prime-minister and party president of the National Liberal Party. As a former Defence Minister and Chief of the Joint Staff he was considered a personal favourite of president Iohannis. They protested the decision by calling it surprising and unjustified. However, they both said that the state would not boycott Austria – this separates them from the more radical and extremist discourse of the moment[18]

Mr Iohannis and Mr Ciucă[19] are unlikely to shape future debates, particularly in the next multi-electoral year of 2024. Slow-talking, evasive, aloof and sometimes arrogant with the press, Mr Iohannis was never a very good campaign-trail politician. In the last few years he has also become less and less inclined to communicate with the media, becoming infamous for his unwillingness to take questions. Mr Ciucă is even less of a campaign politician, having held no political office before his nomination as defence minister and having never competed in national elections. He leveraged his good personal relation with the president and his military reputation to ensure his position but his oratorical talents are limited at best.

Unencumbered by diplomatic obligations, several other major politicians, on the other hand, spoke in ways that were occasionally hard to differentiate from the far-right discourse, insulting Austria and making bold but unsubstantiated threats underscoring a position that was hardly conducive to eventual success.

Rareș Bogdan, a Liberal MEP (affiliated to EPP) considered Austria’s position on the Schengen issue an unacceptable „slap in the face” (saying that Romanians must not remain on their knees[20]), a humiliation to Romania and an act of „holding millions of Romanians hostage”[21]. He compared the decision to “the Vienna dictate[22]” by which Romania had been forced to give territory to Hungary. This is a powerful comparison, as suspicion of Hungary and the Hungarian minority form a cornerstone of Romanian nationalism. To drive the idea home, Rareș called the decision not to grant Romania access to the Schengen space “the worst injustice that has been done to Romania in the last 70 years ”.

His solution was to use an iron fist in a velvet glove[23]. He claimed/threatened that Austria “will bear the consequences”. Also, he called the attitude of Chancellor Nehammer “absolutely racist.”[24].

Several key statements were made during a speech in the European Parliament[25] going against the custom of restricting the use of nationalistic discourse to Romania only.

Marcel Ciolacu, president of the Social Democratic Party (S&D) and president of the lower Chamber of Parliament, had a more moderate tone, choosing mainly to criticise (President Klaus Iohannis’) foreign policy strategies. Nevertheless, he strongly condemned Austria’s position even suggesting that: “You cannot turn your back on the European Commission and the decision of the Commission, the European Parliament… you turn your back out of a purely internal electoral interest of your own. Then you have no place in Europe”[26].

Sorin Grindeanu is the Minister of Transport and Infrastructure in the Nicolae Ciucă government and former Prime Minister. His seniority and track record within SDP make him a possible presidential candidate from the party in 2024. He announced that transportation companies coordinated by his Ministry would no longer work with the Romanian subsidiary of Austria’s Erste Group. Since the legality of using these companies as external policy tools is dubious, he had to claim that [suddenly] they had discovered that commercial conditions were not favourable.[27] It is important to note that he does not seem to have followed through with the threats and the general strategy of boycot[28]. Thus, his declarations appear to be mere internal posturing, with no diplomatic benefits.

Mircea Geoană, Deputy Secretary General of NATO and possible presidential candidate in 2024, also spoke on the issue offering a mix of radical and moderate ideas, blended into evasive, diplomatic language. In a(n) (unprompted) five-minute speech recorded on YouTube[29], with the NATO logo and EU flag in the background, he insisted on a list of commitments or promises allegedly made by the EU to Romania and never fulfilled. These include “automated entry to Schengen after 5 years, with no CVM”, “subventions to farmers equal to those in the EU after an [unspecified] interval of time”, Romania’s inclusion in three pan-European transportation corridors. He goes on to say that the anger and frustration surrounding the Schengen issue are just the last drop of water in a glass that was already full due to the EU delivering something else than what was negotiated. This part is so far a textbook example of the narrative that the West has abandoned Romania. And from the height of his high diplomatic position and credentials, Geoană gives legitimacy to this narrative, choosing to take significant risks in terms of potential loss of credibility with his NATO colleagues through this veiled display of political nationalism/ populism for a domestic audience, in exchange for political gain. Going further, when he proposes solutions, we see that these are not expected from Europe, but from the local political class. This allows Mr Geoană to “dance” between two narratives already common in the political debate. One would say that Romania has an essentially treasonous political elite that works hand-in-hand with the foreign interests while the other says that Romania has a highly incompetent elite that is unable to leverage the benefits of joining the EU. The first narrative is obviously nationalistic, while the second is somewhat pro-EU[30]; but both are populist in that they oppose a corrupt elite to a virtuous people[1] [31].

Mr Geoană has held similar positions in other appearances and is generally on a campaign to raise his profile in Romania, with marked populist-nationalist accents overlapping pro-Western messages. This ‘campaign’ includes appearances on Prima TV[32], Europa FM[33], B1 TV[34]. He has also held a number of anniversary speeches in Romanian[35]. His appearances follow a certain pattern that includes (ab)using NATO and EU symbols in the background, even when he speaks in no official quality, and taking part in a vast array of shows including a sui generis cooking-cum-politics talk-show[36] and an appearance on Marius Tucă Show[37] a niche talk-show that also hosts anti-Western conspiracist voices like journalist Ion Cristoiu or lawyer Dan Chitic and ultra-nationalist president of the Romanian Academy Ioan Aurel Pop.

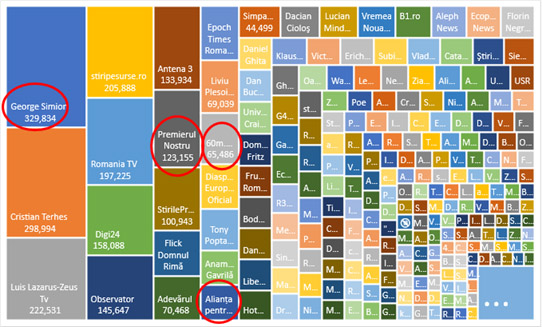

Such pandering to the nationalist electorate was unable to sway attention to the mainstream parties. Facebook channels close to the far-right anti-Ukraine party AUR (circled red in the graph below) gathered most engagements. Nationalist ultraconservative unaffiliated MEP Cristian Terhes was also able to gather engagement. He is not pro-Kremlin or anti-Ukraine but, after the Schengen scandal, he has been able to negotiate a position of lead candidate for AUR at the next EU Parliament elections[38]. Luis Lazarus, a pro-Kremlin online media personality ranks third. Mainstream parties are essentially missing from the conversation – we will see how the Social-Democrats tried to remedy that in the next case study.

Data: Crowdtangle. Graph: Global Focus. Previously featured in

“Monitoring report on the evolution of the main pro-Kremlin voices on Facebook.

Early warning”[39]

Case Study 2: Mainstream reactions to the Bystroye debate

Since 1989, there have been three major disputes that have strained relations between Ukraine and Romania. Two of these disputes seemed to have been resolved before the war began.

The issue of the continental plateau of the Serpent Island has been resolved through international arbitration in a manner satisfactory to Romania. Also, in recent years, the issue of the Bystroye Canal, which the Ukrainian side wants to develop further for navigation, has largely subsided. Developing the Canal was likely to affect the UNESCO heritage site in the Danube Delta on the Romanian side. Romania used all diplomatic and legal means under international law to prevent the deepening and enlarging of the canal.

Only the issue of the treatment of the Romanian minority in Ukraine remained unresolved. But there were hopes for progress as Ukraine received a clear EU perspective, such that it would enact legislation that would be friendlier to minorities due to both European pressure and the sense of community brought about by the war against Russia.

As of the beginning of 2023, both the minority law issue and the Bystroye issue have been relaunched. Neither state is entirely innocent. Ukraine made decisions without transparency and consultations, generating legitimate concerns from neighbours. Romania reacted disproportionately, going beyond diplomatic exchanges (in which a favourable outcome could easily have been anticipated, given the international law and its status as an EU member) and chose to create an internal scandal, through unusually long and vocal MFA communiques.

In a previous report[40] we have shown how the minority law issue did not have a significant impact in society. The situation with the Bystroye issue is rather different. As evinced by all monitoring tools used for this screening[41] discussion about the Bystroye issue brought about a significant increase of engagement on the topic of Ukraine. Unfortunately, the public debate was dominated, once again, by the far-right and pro-Kremlin actors, while mainstream actors either kept a prudent distance (the Liberals) or tried, once again, to follow the example of the far-right AUR party in creating hostility against Ukraine (the Social Democrats).

Main political positions

President Klaus Iohannis, speaking very late in the course of events, at the B9 summit where he met US president JoeBiden, acknowledged the worries about the Danube Delta but advised government institutions to refrain from making rash decisions before having all the information. In this context, he declared “I absolutely do not want to tolerate works that endanger the biodiversity of the Danube Delta, but neither can I agree that it is good to get carried away without knowing exactly what we are talking about here.”[42] He was followed in his conciliation efforts by Liberal prime-minister Nicolae Ciucă who refrained from making any specific accusations[43]. Perhapsa small triumph of moderation is also that nationalist MEP Rareș Bogdan was not a leading voice in the debate.

Marcel Ciolacu, president of the Social Democratic Party (S&D) and president of the lower Chamber of Parliament had a prudent yet nationalistic attitude on the Bystroye issue. His party sponsored a Facebook post claiming that: “We will protect with all our strength the heritage of future generations!”. The language is reminiscent of rhetoric used when speaking about the defence of national territory, rather than loss of water.

Sorin Grindeanu, Social-Democratminister for transportation, published a photo of three ships able to measure the depth of the Bystroye Canal (in order to test whether Ukrainian claims are correct) saying “We are ready! Three AFDJ Galați vessels – equipped for measuring the depth of waterways – are waiting for acceptance to take measurements on the Bystroye Canal”[44]. This could be interpreted as dog-whistling. Moderate voters might read it as a mere showcasing of capabilities. However, since nobody has ever challenged that Romania is able to measure the depth of the Danube, it could also be seen by nationalist voters as hostile to Ukraine, as a signal that the Ministry can measure the depth of Danube but is somehow not allowed (by Ukraine, by the Liberals, etc). His position mirrors the position of his party leader, suggesting that the Social-Democrats were both courting nationalist voters (potentially going for the AUR electorate) and trying to outmanoeuvre the Liberals[45].

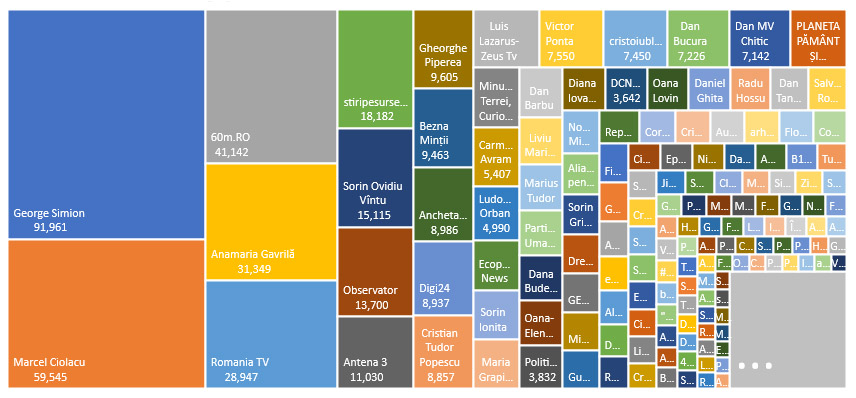

The conversation on Facebook, the main social network for political debate, is authoritatively dominated by current and former members of the far-right AUR party and affiliated media; these include party president George Simion, former AUR MP Anamaria Gavrilă and AUR-Aligned website 60m.RO. These three gather more than 164,000 engagements. In second place the Social-Democrats are represented by party president Marcel Ciolacu who gathers almost 60 000 impressions.

Data: Crowdtangle[46]. Graph: GlobalFocus

The two parties use different strategies. AUR seems to attract engagement organically[47] and does not use Facebook ads[48]. As such, they try to promote some of the leaders and influencers including co-president Claudiu Târziu and comedian Mugur Mihăiescu.

By comparison, the Social-Democrats have tried to boost only the image of the party president, for which they have spent 2,ooo to 3,000 EUR on ads targeted at an audience of Romanians, 35+ years old, resulting in 1 million engagements. The purpose seems to be to have Mr Ciolacu and Mr Simon roughly on a par with each other, perhaps considering that in 2024 the two may both run for presidency.

About one in five posts about Ukraine touches on the topic of Bystroye and in terms of engagement almost one of two engagements on Ukraine comes from posts related to Bystroye in the period illustrated in the graph.

Impact on perceptions of Russia and Ukraine

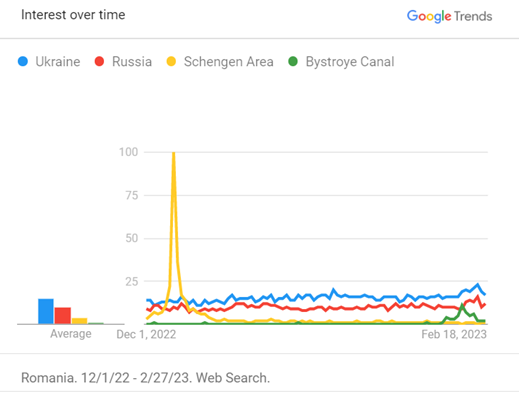

At this point we have no polls to assess the impact on the population of this new situation where anti-Ukraine actors dominate the debate and politicians follow suit. Nevertheless, a look on Trends[49], Google’s tool for evaluating the number of online searches on its search engine will shed some light on the online interest created by these topics.

The Schengen issue was a major national debate, dwarfing any discussion on the war. Far-right actors made some attempts to connect it to the war, for example claiming that Romania should be somehow rewarded for supporting Ukraine. Nevertheless, the (online) public opinion does not appear to have made a connection.

The Bystroye debate is gathering far less interest than the Schengen debate but it does appear to have some influence on the interest in Ukraine and Russia. It is difficult to draw a final conclusion, as around this time there are also heightened tensions between Russia and Moldova. Nevertheless there was at least one day when interest in the Republic of Moldova[50] was still low, while interest in the Bystroye issue is peaking and interest in Russia and Ukraine is already increasing; this strongly suggests that the debate on Bystroye, while less relevant at the national level than the Schengen debate, had an impact on the active interest around the Ukraine-Russia war.

This report is part of an international research project financed by USAID, coordinated by the International Republican Institute’s (IRI) Beacon Project on countering Russian Disinformation and Propaganda. The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of IRI.

[1] Member of the Social Democratic Party, affiliated to S&D in the European Parliament.

[2] Member of the Social Democratic Party, affiliated to S&D in the European Parliament. For his opinions see: https://www.g4media.ro/psd-a-dat-startul-companiei-electorale-cu-un-discurs-nationalist-codrin-stefanescu-psd-e-singurul-partid-romanesc-singurul-partid-nefinantat-din-strainatate.html

[3] https://www.vice.com/ro/article/xyk7jw/declaratii-penibile-leon-danaila

[4] Member of the National Liberal Party, affiliated to EPP

[5] https://www.paginademedia.ro/2014/06/psd-vrea-sa-inregistreze-mandri-ca-suntem-romani-la-osim/

[6] https://www.romania-insider.com/comment-fall-romanian-leader-liviu-dragnea

[7]Austria successfully vetoed Romania’s Schengen accession on purely political grounds ahead of important domestic elections, though the EU consensus was that Bucharest had long fulfilled all required conditions; this has created strong backlash in Romania against Austria and Austrian companies and has arguably boosted anti-Western discourse.

[8] Ukraine revised some of its laws on ethnic minorities at the end of last year as part of its EU accession efforts, but on this occasion failed to withdraw certain regulations, especially regarding education, which Romania had denounced as discriminatory and falling short of EU standards. The Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned this failure in strong language, as well as the absence of prior consultation with the Romanian minority.

[9] Ukraine was reported by various government institutions in Bucharest to have resumed attempts at changing the course and depth of the Bystroye Canal, which in the past have drawn condemnation from Romania and from competent international bodies given the potential negative impact of such measures on the Danube Delta.

[10] https://www.mae.ro/node/60649, https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-esential-26086786-romania-nu-este-acord-ucraina-faca-lucrari-dragare-canalul-bastroe-anuntul-ministerului-externe.htm

[11] Engagement is any kind of reaction, including comments and shares. It is a more relevant measure than views, since a post will be shown on someone’s stream based on the decision of algorithms, and the viewer may or may not read it.

[12] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/06/15/romania-local-elections-old-guard/

[13] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45779107

[14] Such a strategy was used during the COVID pandemic, arguably with disastruous results: politicians took some restrictive measures while at the same time amply signalling how unhappy they were with the measures they themselves were taking.

[15] Originated by Romania’s failure to enter the Schengen space as a result of Austrian opposition.

[16] https://www.global-focus.eu/2023/01/monitoring-report-on-the-evolution-of-the-main-pro-kremlin-voices-on-facebook-early-warning/

[17] It is not the first time that Romania fails to join the Schengen space but this time, after the EU lifted the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism, the Romanian authorities were very optimistic and created a strong expectation that Romania will finally join. While Austria’s decision to threaten a veto was generally seen as highly unfair, the President and the Government were also criticised for creating false hopes.

[18] We do not discuss here if this was or not the right diplomatic decision.

[19] Klaus Iohannis cannot run for the Presidency for a third term. Nicolae Ciucă, by virtue of his position in the party, may end up as the Liberal candidate

[20] https://www.digi24.ro/video/rares-bogdan-despre-schengen-am-stat-suficient-in-genunchi-2124705

[21] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bs-n-Jcqhvw&embeds_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F&feature=emb_logo

[22] https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_XXVIII/407-412.pdf

[23] https://www.digi24.ro/video/rares-bogdan-despre-schengen-am-stat-suficient-in-genunchi-2124705

[24] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bs-n-Jcqhvw&embeds_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F&feature=emb_logo

[25] idem

[26] https://www.antena3.ro/politica/marcel-ciolacu-dezvaluie-ce-greseli-s-au-facut-in-demersul-aderarii-romaniei-la-schengen-665518.html. Emphasis by GlobalFocus.

[27] http://stiri.tvr.ro/grindeanu–companiile-din-subordinea-mt-si-au-anuntat-intentia-de-a-si-muta-conturile-la-o-banca-romaneasca–ciolacu–romania-trebuie-sa-aiba-o-strategie-de-invingator-in-privinta-aderarii-la-schengen_920545.html#view

[28] https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-politic-25964903-live-iohannis-declaratii-inaintea-consiliului-european-unde-vrea-discute-despre-blocarea-aderararii-romaniei-schengen.htm

[29] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48R9BHVOTzo

[30] Done systematically, such a discourse may be interpreted as an effort of de-radicalisation made by recognising some radical ideas. But at this stage we cannot differentiate between populism and de-radicalisation in Mr Geoană’s evasive speeches.

[31] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/feb/17/problem-populism-syriza-podemos-dark-side-europe

[32] https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=2P6XRhDpPUc

[33] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IB3r0Gx4aNc

[34] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qr92DLmhsbk&t=4s

[35] Including for Mircea Carp (Radio Free Europe journalist), Iuliu Maniu (major interwar politicians) as well as the freeing from slavery of the Roma population, https://www.youtube.com/@MirceaGeoanaOfficial/videos

[36] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QKvqvbYJjmE

[37] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8kbx-8SIwCs

[38] https://www.g4media.ro/simion-eurodeputatul-cristian-terhes-va-conduce-lista-aur-la-europarlamentarele-din-2024-vrem-ca-cele-doua-partide-care-reprezinta-sistemul-psd-si-pnl-sa-nu-mai-ia-impreuna-50.html

[39] https://www.global-focus.eu/2023/01/monitoring-report-on-the-evolution-of-the-main-pro-kremlin-voices-on-facebook-early-warning/

[40] https://www.global-focus.eu/2023/02/pro-russian-voices-legitimised-in-the-context-of-romanian-ukrainian-tensions-on-minorities-in-bukovina/

[41] Crowdtangle for social media, Pulsar for online media and Google trends for public interest expressed in online searches.

[42] VIDEO Prima reacție a lui Iohannis în scandalul Bâstroe: Cei care au încercat să facă o mare problemă din asta nu cred că au înțeles miza acestei perioade – HotNews.ro

[43] Nicolae Ciucă, despre canalul Bâstroe: “O să fie sesizată Comisia Europeană” (antena3.ro)

[44] Sorin Grindeanu: Trei nave așteaptă să facă măsurători pe Bâstroe (cotidianul.ro)

[45] Liberals hold the Presidency, the PM office and the MFA. As such their margin for provocation is smaller.

[46] https://apps.crowdtangle.com/search?includedLanguages=ro&platform=facebook&postTypes=&producerTypes=3,1,2&q=B%C3%A2stroe%20OR%20B%C3%A2stroie%20OR%20B%C3%AEstroe%20OR%20B%C3%AEstroie%20OR%20Bstroe%20OR%20Bstroie%20OR%20((delta%20OR%20deltei%20OR%20dunare%20OR%20dun%C4%83re)%20AND%20(Ucraina%20OR%20Ucrainei%20OR%20Ucrainean%20OR%20Ucraineni%20OR%20Ucrainian%20OR%20Ucrainieni%20OR%20Ucrainienilor%20OR%20Ucrainenilor))&sortBy=score&sortOrder=desc&timeframe=7days

[47] Using party organisations to boost engagement cannot be excluded.

[48] Technically 60M has promoted an ad to an article quoting from Ionuț Stroe where he accuses AUR of extremism https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/?active_status=all&ad_type=political_and_issue_ads&country=RO&id=952920249048395&view_all_page_id=109849657256655&search_type=page&media_type=all

[49] https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2022-12-01%202023-02-27&geo=RO&q=%2Fm%2F07t21,%2Fm%2F06bnz,%2Fm%2F05fc5kf,%2Fm%2F03pnmm

[50] The Republic of Moldova is not present on the graph for purposes of clarity.