By Alexandru Bălășescu | Hong Kong

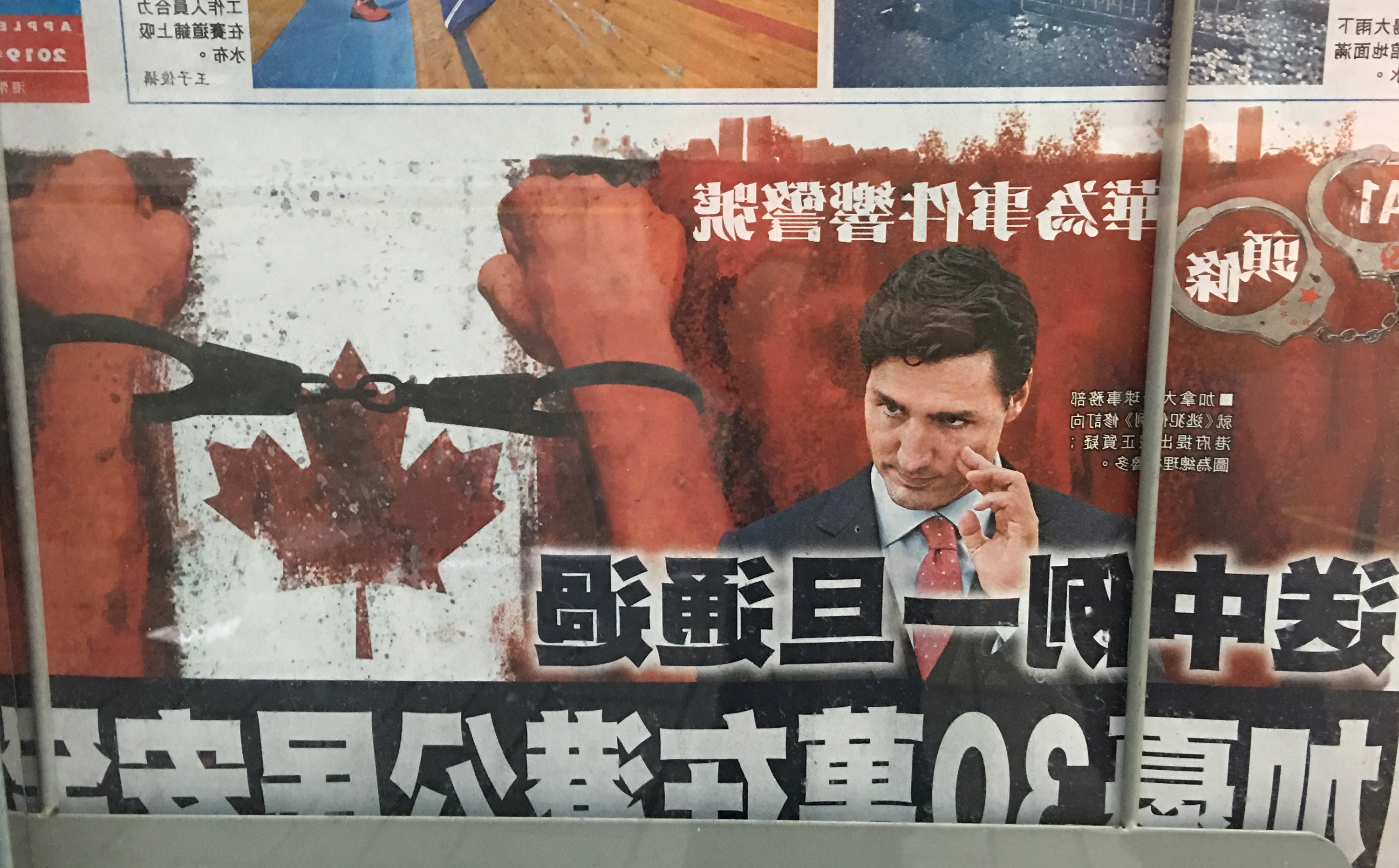

On 20 April, barely a week into settling in Hong Kong, my attention was captured by the front page of a local newspaper, featuring a photo-collage with a handcuffed wrist and Trudeau on the background of the Chinese and Canadian flags (see photo). But without understanding the writing, the meaning was anybody’s guess.

Mine was that it was related to the arrest of Mrs. Meng, the CFO of Huawei in Canada (because I was coming from Vancouver, where I had spent the prior 5 years). I sent the picture back to my friends in Canada, and one of the answers was: “It’s funny to see Trudeau as bad boy.” I also asked for a translation, and it seemed that the intention was to portray Trudeau rather as a sad boy, caught in the possible conundrum that the now-infamous Hong Kong extradition bill would generate.

The concern expressed about it became the spark for the summer of discontent and protests in Hong Kong: China would use the bill in order to arbitrarily arrest and deport Hong Kongers to the Mainland. With somewhere around 300,000 Canadian citizens living in Hong Kong, many of them of Hong Kong descent, and with the ongoing chill in Sino-Canadian relations, Trudeau, the newspaper argued, would have plenty of reasons to be concerned.

The bill was proposed following a murder case: a Hong Kong student allegedly killed his girlfriend in a Taiwan hotel and flew back to Hong Kong. The case required the accused to be extradited to Taiwan, but the process was delayed by the lack of any agreement between Taiwan, Hong Kong and mainland China. The student was arrested on money-laundering charges in Hong Kong, and he is scheduled to be released on October 23.

However, many Hong Kongers viewed the proposed bill as yet another step towards mainland-Chinese encroachment on their rights, opening, in their opinion, the possibility of politically-motivated random arrests in Hong Kong. To a lesser extent, similar unease was provoked by the opening of the high-speed train terminal to the mainland, where the mainland police have full power of operation.

Photo: Alexandru Balasescu, Hong Kong

Thanks to the Chinese-British agreement, Hong Kong was granted special status after the handover to the Beijing government in 1997, allowing the city to maintain its own constitution and government until 2047. This marked the beginning of the ‘one country, two systems’ form of government promoted by Beijing in its relationship with Macau, Hong Kong, and possibly, in Beijing’s view of the future, Taiwan.

Currently, Beijing has a special Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the State Council that serves as an intermediary between the People’s Republic of China government in Beijing and Hong Kong’s legislation body. The director of the office is Zhang Xiaoming. The Hong Kong government leader, also known as the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, is Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor.

The Hong Kong Chief Executive is elected by a 1200-strong body of electors; the electoral system was challenged on the streets in 2014 by parts of the Hong Kong population who demanded its replacement with universal suffrage. The movement, known as the Umbrella Revolution – due to the fact that the protesters used umbrellas to protect from both rain and water cannons and tear-gas – was crushed, while some of its leaders were arrested and received prison sentences.

In late May this year, barely three months after launching a public consultation on the extradition bill, Carrie Lam announced that it would be brought to the executive floor for voting. On 9 June, protesters massed in Central Hong Kong in a movement more than one million strong (estimations regarding the size of the crowd varies depending on the source of the estimate). The protests were meant to make the legislators aware of the fact that a significant part of the population was opposed to the bill and/or unhappy with the public consultation process.

From the British colonial period, Hong Kong inherited a network of neighbourhood committees meant to participate in the consultations for policy decisions. This was meant to compensate for the intrinsic lack of legitimacy of the colonial system. In the case of the extradition bill, it appears that this network was only partially consulted, if at all.

In the evening of 9 June, after the protesters broke up, Carrie Lam made a public announcement that voting on the bill will go forward. This marked the start of a long summer of protests with ramifications far beyond Hong Kong.

Facts

Initially the protests were peaceful albeit sizeable, and the protesters used white T-shirts as a sign of their peaceful intent. The bill was scheduled for a second reading in July, but on Monday 1 July, the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese law, the violence escalated, and the protesters broke and entered into the Legislative Council building of Hong Kong (LEGCO), vandalising its interior.

Police forces used tear gas and rubber bullets against the protesters, and a spiral of violence swept the Hong Kong protests. By this time, the protesters had changed their garments’ colour to black. Carrie Lam declared the bill “dead” but refused to officially withdraw it.

The city entered into a ballet of protests, police interventions, and press conferences with an almost ritualistic character. The protesters would occupy streets and vital points during the weekend, clashing with the police. The Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam would speak to the public through the press conferences organised every Tuesday afternoon. People would wait for them anxiously.

Hong Kong protests and their trans-national ramifications indicate that we are just at the beginning of the period of political globalisation. This won’t be a walk in the park.

However, until early September nothing of significance was announced, and the violence gradually increased and ramified under different forms. Hong Kong police started arresting participants in the protests, among them voices that became prominent during the movement. One important turning point was the attack at the Yuen Long MTR station (the Hong Kong subway), when white-clad mobs indiscriminately beat passengers and people who they identified as protesters. The attackers’ identity remained unknown, but there has been speculation that they were members of Triads with links to Beijing.

The protest evolved as a leaderless movement with five demands: the official withdrawal of the bill, unconditional amnesty for the arrested, an independent inquiry into police violence, a re-start of the electoral reform process, and an official recognition of the movements as protests and not ‘riots’.

Hong Kong’s Leader Carrie Lam became the central focus of protesters’ demands, as she was viewed as the person who could defuse the tension. However, her lack of action for months in a row created an escalation of violence, with police forces intervening every weekend, using tear gas, rubber bullets and cannons firing dyed water to disperse the increasingly resistant and resilient crowd.

Unavoidably this translated into hostility towards the police forces itself, and later, sadly, towards their families. The police forces expressed a justified discontent, seeing themselves caught in the middle of a political crisis with solutions that did not depend on their actions. On the contrary, its continuation threatened to deepen the divide. Apartments owned by policemen were attacked from the streets with stones. At the start of the school year, professors were worried about a backlash from students against the daughters and sons of police force personnel.

Highlights

The techniques used in protests evolved.

The crowds could be classified into three or four different types of participants: the front lines, fully equipped to face the police actions; the mass; the helpers; and the cleaners, coming at the end of the columns to clean up – in order, so they said, not to put any more strain on the municipality workers.

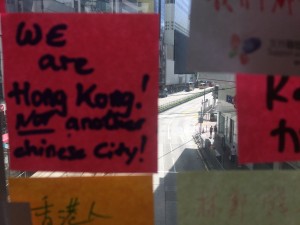

The use of ‘Lennon Walls’ – stickers and posters with grievances and announcements on different walls in the city – was quickly adopted around the world in support of the Hong Kong protesters.

The protesters occupied the airport in mid-August and managed to block air traffic for two days. This was a major turning point in the events, marking the first time when a police officer pulled his gun in order to protect himself from the menacing crowd. The occupation of the airport ended after two days, but one of the consequences, besides ruining the plans of a lot of travelers, was the resignation of Cathay Air CEO Rupert Hogg and his deputy.

Earlier in the summer, the mainland-Chinese authorities asked for the identification of any Cathay personnel who may have participated in the protests, and stated that they would not be allowed to board airplanes that travels through Chinese airspace. This affected more than 60 percent of all Cathay’s air traffic. The authorities also asked that the personnel be identified and that the company instructs them not to partake in the protests, physically or otherwise. CEO Hogg initially resisted, saying that he could “not even dream of tell the company’s employees what to think”, but afterwards complied with the demands, and subsequently resigned.

The occupation of the airport also marked the first time when the crowds turned violent against a person who they identified as an ‘infiltrator’ from the Chinese mainland, whom they detained and held for a few hours. The person, later identified as a journalist from Beijing, famously said: “I support the Hong Kong Police. Now you can beat me.” We’ll return to this.

Carrie Lam’s unchanged position and her refusal to address any of the demands while appealing for calm were perceived as indicators of her dependency on Beijing. Speculation on her lack of political power replaced speculation regarding her lack of political will.

The situation seemed to have come to a complete halt.

On 27 August, after a weekend of ‘unprecedented’ violence in the city that on one side saw police forces and the population sympathetic to Beijing, and on the other side the protesters, continually advised by stakeholders in Hong Kong business, Lam agreed to meet protesters’ delegates. On 2 September, Reuters published a leaked audio recording in which one can hear her saying she would quit if given a choice. The audio suggested that the speculation about Lam’s dependency on Beijing’s decisions was accurate. Immediately after the leak, Carrie Lam agreed to meet one of the protesters’ five demands; she officially withdrew the bill.

However, the protesters stated that this was too little, too late, and the protests’ dynamic continued, with the violence hitting a peak during and after 1 October, on the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China’s foundation. Police fired five live rounds, hitting one teenager in the chest. As violence builds upon violence, there is no end in sight.

People

During the course of the protests, clashes emerged between the protesters and that part of the local population whose roots lie in recent immigration and relocation from the mainland, especially in North Point, a neighbourhood in the north-eastern part of the island containing Chinese migrants, mainly from Fujian province. After 1 October, attacks targeting Chinese-related businesses increased in frequency and violence.

A Chinese government programme, put in place in 1980 for Hong Kong and Macau, allows a quota of 150 people a day to receive a one-way residence permit and move permanently to the two provinces. With a population of 8 million, it seemed easy for Hong Kong to absorb the new-comers, but over the years the effects of this migration have become increasingly visible, especially in matters of political choices.

The process is entirely controlled by Beijing: Hong Kong authorities do not review the applications for permits. Concerns have been raised recently regarding both the increasing number of arrivals (last year the quota was exceeded, while in earlier periods it was not used up completely), as well as the origin, age and scope of the migrants. A sharp rise in the 45-54 age segment was registered, raising eyebrows among Hong Kongers.

Hong Kong’s population itself is multilayered, containing locals with origins in the fishing villages of old Hong Kong, as well as Chinese mainlanders, mostly from Guangzhou, who arrived in waves during the past century – initially in search for better economic opportunities, or moving away from the mainland during Mao’s revolution. They contributed significantly to the prosperity of the island, and to the creation of the financial and trade systems that made the island an attractive destination for South-East Asians and Europeans alike.

The current protests have revealed multiple social and political rifts, although these do not necessarily stem from a sole criterion. Although age is seen to be, and presented by many as the main rift, this is slightly inaccurate.

The protesters combine young students and even younger high-schoolers, young and middle-aged working classes, liberal-minded middle classes of all ages, and sometimes the elderly. They seem to be united on the one hand by concerns regarding social and financial inequality – where housing prices are central – and on the other hand by a perception of having no future, either caused by a lack of financial security, or by the perceived unavoidable loss of individual freedoms come 2047. They feel that the Beijing government has prematurely started to encroach on their civil liberties.

The pro-government population in Hong Kong is perhaps mostly silent on the street, save the newly-migrated Chinese population mentioned above. Owners of small businesses, Chinese patriotic students or office workers, they organise counter-protests and gatherings of their own, that more often than not turn into direct confrontations with anti-government protesters.

The pro-Chinese Hong Kongers are mostly conservative-minded, middle-aged or older, established and financially secure, whose calculations may be summarised as ‘why rock the boat?’. Origins seem to count less among this group, and they include people who left China in the 1950s and 1960s, but who are now pro-Chinese.

The rifts traverse families, friendships and neighbourhoods, and sometimes people avoid talking openly about their political choices in order to maintain those ties. This may not be the best solution when the society is in dire need of dialogue and reciprocal understanding.

Rhetoric

The multiple stakeholders involved in the protests have multiple characterizations of the protesters, opinions which in fact reveal their own political stance.

From the beginning, the Hong Kong government portrayed the protests as riots, and this label was one of the contentious points between the two sides. From the government’s viewpoint, this allowed them to strategically retreat from the political dispute for a long time, and to rely solely on the police force in order to restore order. In their view, there is no political solution for riots that by definition are illegal. Over the course of the summer, the police did not approve many of the demands to organise protests, including those on 1 October, which by default placed the protesters outside the law.

The Chinese authorities swung between restraint and menace. Beijing labeled the protesters as terrorists, and they compared the movement with the ‘color revolutions’ in Eastern Europe and Ukraine. As a matter of fact, the Netflix documentary Winter on Fire concerning the Ukrainian revolution seems to have been one of the most-watched in Hong Kong. On the weekend of 23-24 August, the protesters organised a human chain along the shores of the Island recalling the Baltic states’ movement for separation from the USSR. This seemed to justify the Chinese authorities’ fears.

Social Media Conversation. Drawing by Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi

The Chinese authorities have also framed at least some of the protesters as separatists. However, there have been no demands which could be interpreted as a move towards independence for Hong Kong, and the Hong Kongers in general are not keen on being an independent state. While there are radical Hong Kong pro-independence groups, they are very small in terms of their size, role, and influence. Both the Chinese authorities and the protesters seek to portray themselves as the real defenders of the ‘one country, two systems’ principle, and both sides have accused the other of violating it.

The Chinese authorities have massed army troops at the border with Hong Kong, and released films showing the army exercising crowd control. The crowds were dressed similarly to the Hong Kong protesters, and during the exercise they were addressed in Cantonese. However, the Chinese authorities argued that these are routine army exercises.

The war of words spilled out internationally, and patriotic Chinese individuals and groups all over the world have taken to defending Beijing’s stance on Hong Kong, and accusing the protesters of being ungrateful, if not influenced by foreign powers that do not understand China and are acting malevolently towards it. Their rhetoric is fascinating, oscillating from portraying Hong Kong as a family member that has gone astray (commonly, a small ungrateful brother contaminated by outside decadent Western values), to directly calling those protesters of Hong Kong origins names that suggest they are not ‘human’ because they do not understand ‘human language’, i.e. Mandarin Chinese.

The family metaphor is particularly important, as one of the critiques that China makes of the West is that of having very permissive family values and a lack of ethics. There are clear calls for the population not to abandon their strong family values for those inspired by the West.

From the side of the protesters, the words against the Hong Kong government and Beijing are equally tough. While Hong Kong’s government and its leader are portrayed as powerless and ‘sell-outs’ to Beijing, the protesters now claim that mainland China has become outright ‘Chinazi’. Meanwhile, mainland-Chinese commentators have been quick to point out that using violence in order to attain political goals goes against the liberal values that the protesters themselves claim to profess.

Many Western commentators have contributed to the image of the events in Hong Kong as similar to that of the ‘colour revolutions’ in Eastern Europe. In fact this does not help the protest movements, and also misses the point.

Hong Kong is not independent of China, nor does it want independence. Moreover, while in the early 2000s the Chinese economy relied heavily on Hong Kong’s financial power, today Hong Kong is only responsible for around 3% of Chinese GDP (down from 20% in the late 1990s). It is true that Hong Kong is still an important gateway role to China, originating in its blend of Western and Eastern values and, ironically, its colonial history.

However, China’s presence today is legally legitimate according to the Sino-British treaty. If we are to make a historical comparison, in fact this moment resembles the expansion of the Soviet Union after the Second World War, and with the replacement of the local elites with those who were subservient to Moscow. However, the mechanisms used by Beijing, with a slow population influx and the careful preparation of mainland students in Hong Kong are much more subtle than the brutal Russian methods of the past century.

As on the streets, the situation is also stalled in the realm of rhetoric, with both sides portraying the other in similar but opposite terms, deepening the rift and making dialogue less and less possible.

Spill-over

Universities around the world receive a significant number of mainland-Chinese students. Commonwealth countries such as Australia or Canada also have a significant student population from Hong Kong, who migrated both after Hong Kong’s handover and more recently. A few campuses in Vancouver, Brisbane, and other university centres clashes have been reported between Hong Kong students who expressed support for the protesters and mainland-Chinese students. Most of the reports have emphasised the mainlanders’ aggression, verbal and physical.

Clashes in Melbourne, Sydney and other university centers have been reported. Beijing has expressed its support for the ‘patriotic behaviour’ of mainland students. Universities have been slow to react, not least because they depend financially on the big influx of students from China, but they have condemned the aggressive behaviour and defended freedom of speech.

After the incident at the airport, the Chinese actress cast in the lead role in Mulan, a future Disney production, tweeted “I support Hong Kong Police. Now you can beat me”. Calls to boycott the film immediately went viral on the internet, even though the film is only scheduled to be released next year.

Photo: Alexandru Balasescu, Hong Kong.

Also during the summer a series of Facebook accounts were closed down by the company on the suspicion that they were fake accounts controlled by Beijing and spreading fake news about the Hong Kong protests around the world. Beijing denied involvement and claimed that this was spontaneous patriotic behaviour by young Chinese, who independently decided to go through the trouble of by-passing the ‘great firewall’ put in place by China (where Facebook is not directly available) in order to voice their discontent about how the Hong Kong situation is portrayed outside China.

It is indeed true that many young mainland Chinese are politically motivated by patriotism and the feeling that their love of their own country is not heard, or too readily interpreted as propaganda.

Smaller nations in the South China Sea, including self-ruled Taiwan, are looking at what is happening in Hong Kong with interest. Solidarity rallies have been organised, and countries like Malaysia questioned the protests’ legality. Concern about how the protests will develop is high, as those nations are aware of being in China’s direct zone of influence.

These are just a few brief examples of how the protests in Hong Kong have spread around the world, revealing an intricate global network of interests, allegiances, and political behaviours that are reshaping the world we live in.

The beginning of political globalisation

Although against the background of the US-Chinese tariff war and slowing economic trade, some commentators are postulating the end of globalisation and wondering what will come next, the Hong Kong protests teach us otherwise.

Yes, we may be in a period in which the unhindered flow of commodities and finance on the so-called free market is slowing down. Under the weight of the tariff wars, fractured regional alliances, local wars and tensions, the fragile system of free markets is taking a destabilising blow.

However, the Hong Kong protests and their trans-national ramifications – from university campus disputes to entertainment boycotts, or backlashes against giant social networks against the background of Beijing’s attempts to attract global public opinion to its side – indicate the fact that we are just at the beginning of the period of political globalisation. This will not be a walk in the park.

What is at stake in Hong Kong today are the basic principles of global governance that we agree upon, or not, for tomorrow.

Beijing’s proposition is a form of governance supported by an advanced technological apparatus of surveillance and control aimed at the preservation of social peace at the expense of a number of individual liberties. This form of governance was famously named by Kai-Fu Lee as ‘techno-utilitarianism’, and postulates a highly regulated social and political space in which prosperity is secured.

The price is unquestioning consent. China’s financial expansion around the world is accompanied by the insertion of its technology in the regions of most importance to it. Will the principles of this techno-utilitarianism also be applied in those regions? And here we circle back to the Huawei scandal and the fears of the mass-scale adoption of Chinese technology in some parts of the world.

One episode in Hong Kong in August is telling, although it went almost unnoticed. In Kowloon (a district of Hong Kong), protesters attacked the newly-installed lamp posts that were equipped with surveillance cameras and data-gathering sensors. The Hong Kong municipality presented those data gathering points as tools that would help the regulation and optimisation of urban traffic. However, the population thinks that they are also being used to gather sensitive data, including related to face recognition, since these particular posts were installed by a Mainland Chinese controlled company. One of them was completely torn down.

We are at an important crossroads: on one hand, techno-utilitarianism is perceived in the West as dangerous and encroaching of individual liberties. On the other hand, democracies stretched to the limit of their principles of individual freedom, combined with the advent of unregulated social media, have given birth to manifestations of populist, totalitarian behaviour in public and political spaces.

The political space in some Western democracies seems to be slowly transforming itself into a perverted form of ‘participant totalitarianism’ powered by social media. The emerging model of political globalism does not closely follow the economic and financial model, but is emerging from the dynamic interaction of finance, economy, technology and political culture. We are still at the beginning of shaping the global political culture of the future, torn between localism, regionalism and globalism.

How we navigate and regulate the mechanisms of consensus-making in public life is up to us: through surveillance and coercion, through continuous publicly debated policies, or through hard ideological dominance based on the exclusion of the other and legitimated by fear and resentment? I hope we will choose wisely.

All the photos in the article, including the main photo, were taken by Alexandru Balasescu.

DR. ALEXANDRU BALASESCU is a cultural anthropologist and his research, writing, and practice are centered on understanding human actions in context (the result of dynamic interactions between culture, technology, economy, religion, gender and sexuality, and institutional practices). He is Associate Faculty at School of Leadership Studies, Royal Roads University, Victoria, BC. Balasescu is the author of “Paris Chic, Tehran Thrills. Aesthetic Bodies Political Subjects”, 2007 and “The Joyous Display of Global Order “(in Romanian) Curtea Veche 2010, and published extensively in international journals.